AI and the Mastery Paradox: When Machines Deny Us the Chance to Grow

In the age of artificial intelligence, many tasks that once required accumulated skill, practice, and error are now handled with ease by machines. From autocorrect and predictive text, to AI-assisted music composition, image generation, or decision-making tools — we are surrounded by systems designed to accelerate, optimize, and sometimes replace.

While these tools promise efficiency, comfort, and capability, there is a growing paradox: the very convenience of AI may rob us of opportunities for mastery, undercutting our psychological growth.

In this post we’ll explore this paradox in the light of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, examine some evidence around AI’s impact on skill development, and suggest ways to design AI so that it challenges rather than infantilises us.

What is the Mastery Paradox?

“Mastery” refers to the process by which someone becomes highly competent in a domain through practice, failure, feedback, iteration, and often struggle.

Mastery isn’t just about result; it is about the path, the internal growth, the identity formed through doing, failing, refining, persisting.

The Mastery Paradox is this:

AI promises enhancement, assistance, and sometimes replacement of human effort. We can offload tasks, get immediate results, rely on suggestions, skip steps. But in doing so, we may lose or reduce the very experiences — the friction, difficulty, learning through doing — that are essential for human growth, self-esteem, identity, and deeper fulfilment. AI might make tasks easier, but at what cost to our capacity to grow, to feel proud, to truly become good at something?

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs & How Mastery Fits

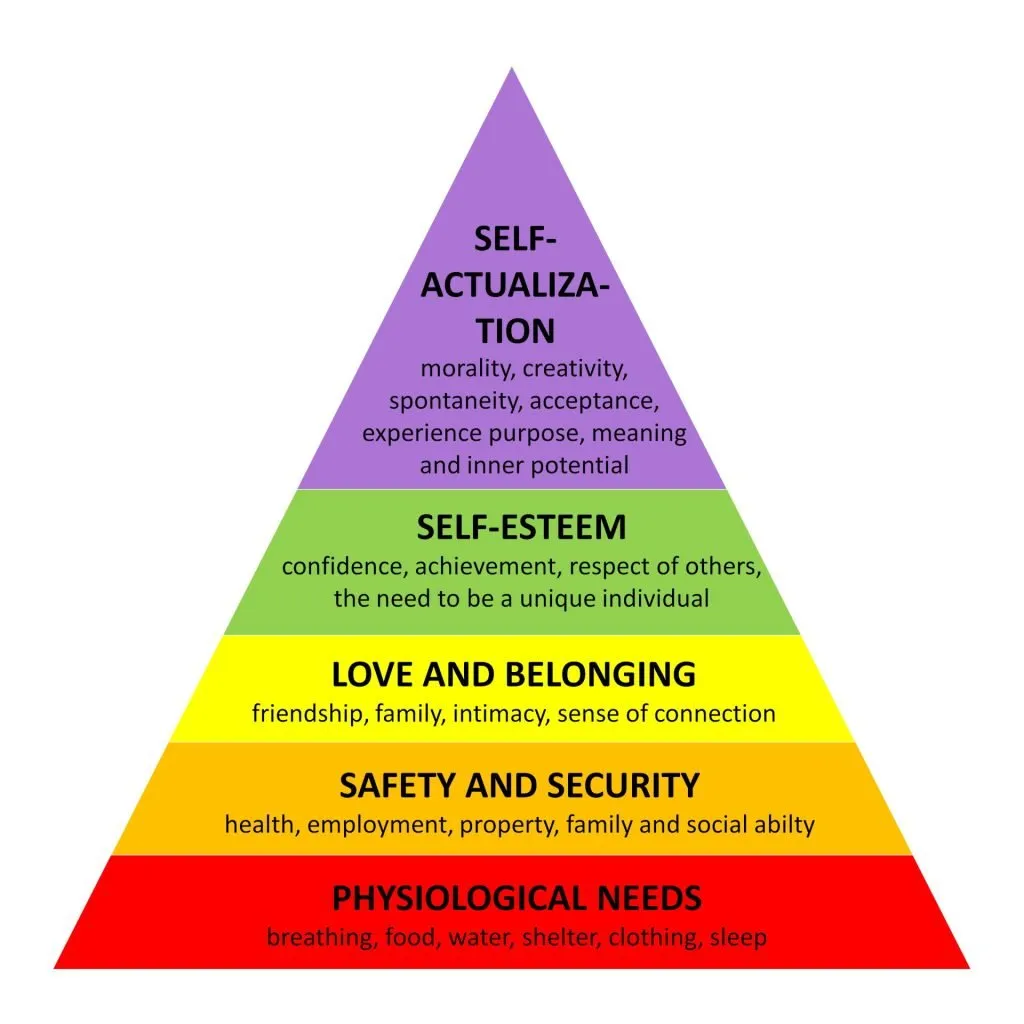

To understand the stakes, we can frame mastery in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Originally proposed by Abraham Maslow, the model has (in its simplest form) five tiers:

- Physiological needs — food, water, rest, basic survival.

- Safety needs — security, stability, order.

- Love / Belongingness — relationships, connection, social bonds.

- Esteem — respect, recognition, confidence, achievement.

- Self-actualization — realizing one’s full potential, seeking personal growth, mastery, peak experiences.

Mastery is squarely in the realm of esteem and self-actualization needs. To feel confident, to feel respected by ourselves and others, to build competence — that requires practice, failure, persistence. To reach self-actualization, one must push beyond comfort, stretching limits, refining capacities.

Now imagine a scenario where AI handles almost everything that could be considered “lower-esteem” effort: writing, planning, composing, content generation, solving, decision-making.

Also imagine if AI systems proactively ensure that our safety and belongingness are satisfied in abundant measure. Those lower levels of the hierarchy become easier to fulfill. People may feel comfortable, secure, socially connected, and less burdened by routine tasks. But that convenience might reduce the friction, the need, the impetus to engage in challenging effort.

If esteem needs are satisfied superficially (via recognition aided by AI) rather than via earned competence, then the path to self-actualization becomes hollow or under-traversed.

Thus, there is a risk: stagnation. Even when lower needs are met, higher needs may not be fulfilled if mastery is bypassed or short-circuited. The journey is as important as the destination — but AI may help us reach certain “levels” of comfort while skipping key growth experiences.

Evidence & Emerging Research

There is already research pointing toward potential downsides of over-reliance on AI or automation, especially in cognitive and skill development. Some relevant findings:

- A study on “Does using artificial intelligence assistance accelerate skill decay …” shows that consistent use of AI assistants may be detrimental to human skill learning and expertise.

- Research on AI tools and critical thinking / cognitive offloading (the tendency to delegate mental operations or thinking to machines) shows that high dependence on AI corresponds with reduced critical thinking ability. For example, a recent study finds that the more people rely on AI tools, the more likely they are to experience decline in independent thinking skills.

- Reports show that frequent AI tool usage is correlated with poorer performance in tasks requiring sustained reasoning when the AI is removed. This suggests that skills may atrophy when the scaffolding is always present. (The “use it or lose it” principle in cognitive skill-acquisition).

This all seems obvious, and the research suggests that the paradox is real, not just theoretical — there is growing empirical concern that AI, especially in its current forms, may reduce the opportunities for people to build deep competence and confidence.

Framing the Paradox via Maslow

Let’s map these observations back onto Maslow’s model:

- Lower levels (physiological, safety, belonging) are being more easily fulfilled by AI-powered convenience — virtual assistants, recommendation systems, social connectivity, even economic automation.

- Esteem needs: recognition, achievement, respect. AI may supply external markers of “success” (likes, status, outputs) even if the underlying competence is shallow. This can lead to inflated esteem or fragile esteem (esteem not built on true ability).

- Self-actualization: the highest growth-oriented psychological need, tied deeply to mastery. When people no longer face or willingly embrace challenge, when effort is minimized, when failure is rare, then growth slows or stops. Self-actualization becomes harder to attain, even if many “lower” needs are more easily met.

The Risk: Infantilization & Loss of Fulfillment

By infantilization, I mean a condition where people are treated (or treat themselves) as if their growth, autonomy, and capability are secondary. AI that does too much for us — removes decision points, polish, error, the need for struggle — can contribute to this. In such a case, people may become dependent, passive recipients of ready-made outputs, rather than active creators and learners.

Fulfillment often comes less from achieving perfection, more from overcoming obstacles, learning what doesn’t work, building confidence, seeing growth over time. If AI removes the friction and friction is essential for growth, then satisfaction may become more shallow, even if life becomes “easier.”

How Might We Design AI to Preserve (or Amplify) Mastery?

If we accept that there is a real mastery paradox, then what concrete changes or safeguards can help us design AI systems (and our use of them) to challenge us rather than replace the developmental path? Here are some proposals:

1. Progressive Autonomy / Gradual Fading of Assistance

Design AI that begins with heavier assistance but gradually steps back as user competence improves. Similar to educational scaffolding: the tool supports until the learner can take over more parts. This ensures that the learner is not forever dependent.

2. Adaptive Challenge

AI systems should not just optimize for speed and efficiency but for the user’s growth curve: provide tasks, problems, or challenges just beyond current ability so that learning is maximized.

3. Transparency & Feedback

Let users see when AI helped, where errors were corrected, what alternatives were rejected, etc. Feedback on what the user did vs what the AI contributed helps preserve the sense of agency and learning.

4. Deliberate Friction

Sometimes friction is good. Allow or design modes in which users must perform certain tasks manually (or partially), even when full automation is possible. Those modes act like “training wheels” but also preserve dry runs.

5. Recognition of Effort, Not Just Outcome

In education, work, creative domains: reward the process, struggles, growth. Systems (including social systems) that praise only the end product risk encouraging shortcuts, polishing rather than substance.

6. Cultivating Meta-skills

Skills like critical thinking, self-confidence, creative problem solving, self-assessment are higher order skills that support mastery. AI tools should aim to strengthen them rather than replace or suppress them.

7. User Literacy & Awareness

Users need to understand what AI is doing, what it is not doing, its limitations. Education/culture around AI use should include cultivating awareness of potential skill decay and encourage “conscious use.”

Possible Objections & Counterpoints

- Efficiency is Valuable: Some will argue that efficiency gains free time and mental energy for higher level pursuits. True: AI can offload mundane tasks and let people focus on what they care about. But there is a risk that “offloaded” tasks are precisely those that build foundational competence and confidence.

- Not Everyone Wants Mastery in Everything: Some people may be content with surface-level skill in many areas rather than deep mastery in a few. There is nothing inherently wrong with that. But the paradox arises when the structure of society or AI options channel choices such that mastery becomes inaccessible or socially undervalued, even when people desire it.

- AI as a Partner, Not Replacement: If AI tools are designed well, they can complement human growth (for example, giving suggestions but requiring human decision). The risk is not AI per se but poorly designed AI or unreflective use.

Conclusion & Call to Action

AI is one of the most powerful tools we have ever made for extending human capability. But it carries with it a paradox: in promising ease, speed, and optimization, it may undercut the very growth that gives life meaning.

Mastery — that journey through uncertainty, failure, iteration, and perseverance — is essential to esteem and self-actualization, that we all ultimately seek.

We need to ensure that AI is designed and used in ways that preserve opportunities for growth: by embedding challenge, preserving friction, emphasizing process, and helping users become more capable, not less.

Questions for reflection or further exploration:

- In which areas of your own life are you already using AI in ways that shortcut growth?

- Can you carve out “no-AI zones” or times for deliberate practice and struggle?

- How might educators, employers, tool-makers incorporate mastery-friendly features into AI systems?

The mastery paradox is not an argument against AI, but a caution: let us shape AI so it enhances not erodes our capacity to become more of what we can be.

AI and the Mastery Paradox: When Machines Deny Us the Chance to Grow

AI is one of the most powerful tools we have ever made for extending human capability. But it carries with it a paradox: in promising ease, speed, and optimization, it may undercut the very growth that gives life meaning. Mastery — that journey through uncertainty, failure, iteration, and perseverance — is essential to esteem and self-actualization, that we all ultimately seek. This article digs into this paradox…