The Destination Adjacency Challenge in Destination Marketing

Destinations often assume a destination is chosen and consumed on its own.

But travel planning rarely works that way. Visitors typically move through a gateway and then stitch together a trip from adjacent destinations that feel logically connected, even if they sit under different administrative boundaries or brands.

That gap between how destinations brand themselves and how visitors actually travel is what many DMOs and place brands refer to as Destination Adjacency Challenge.

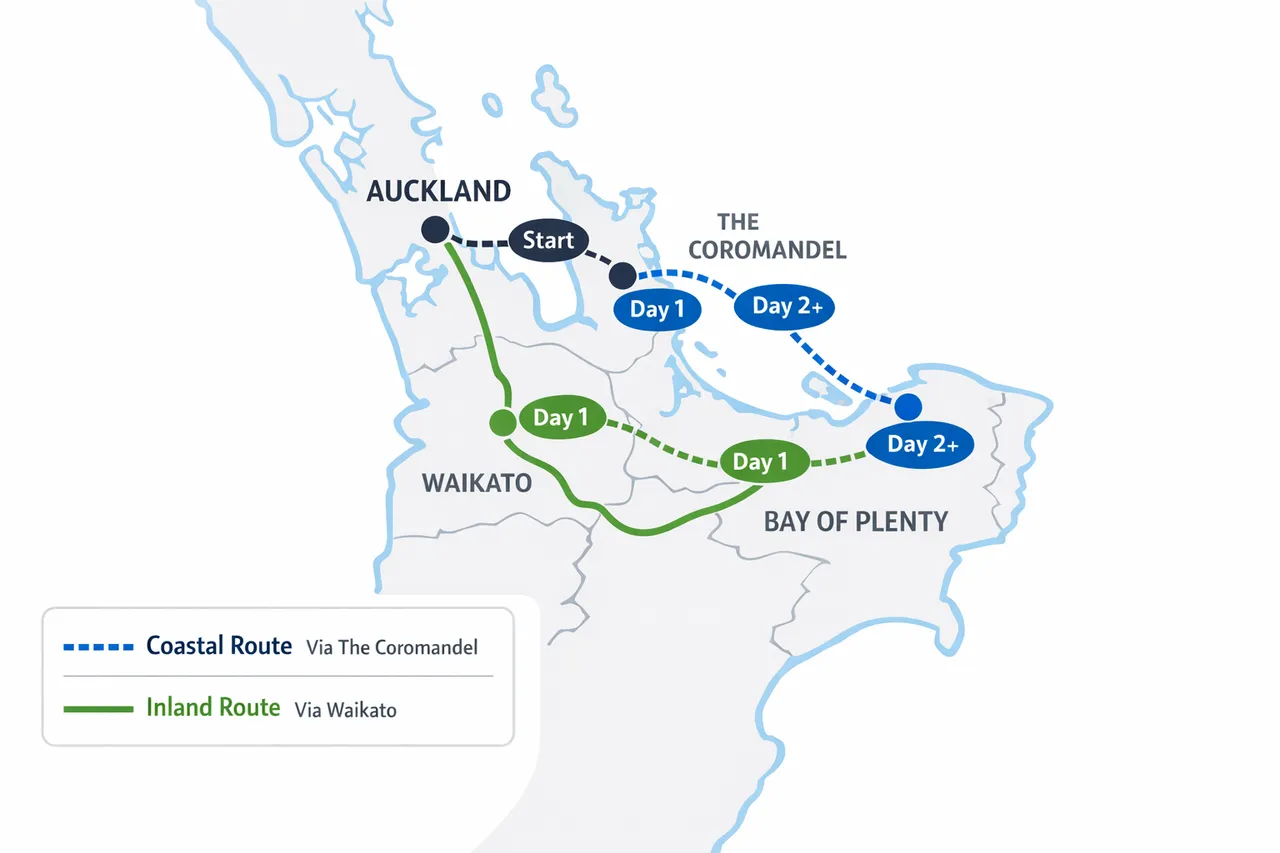

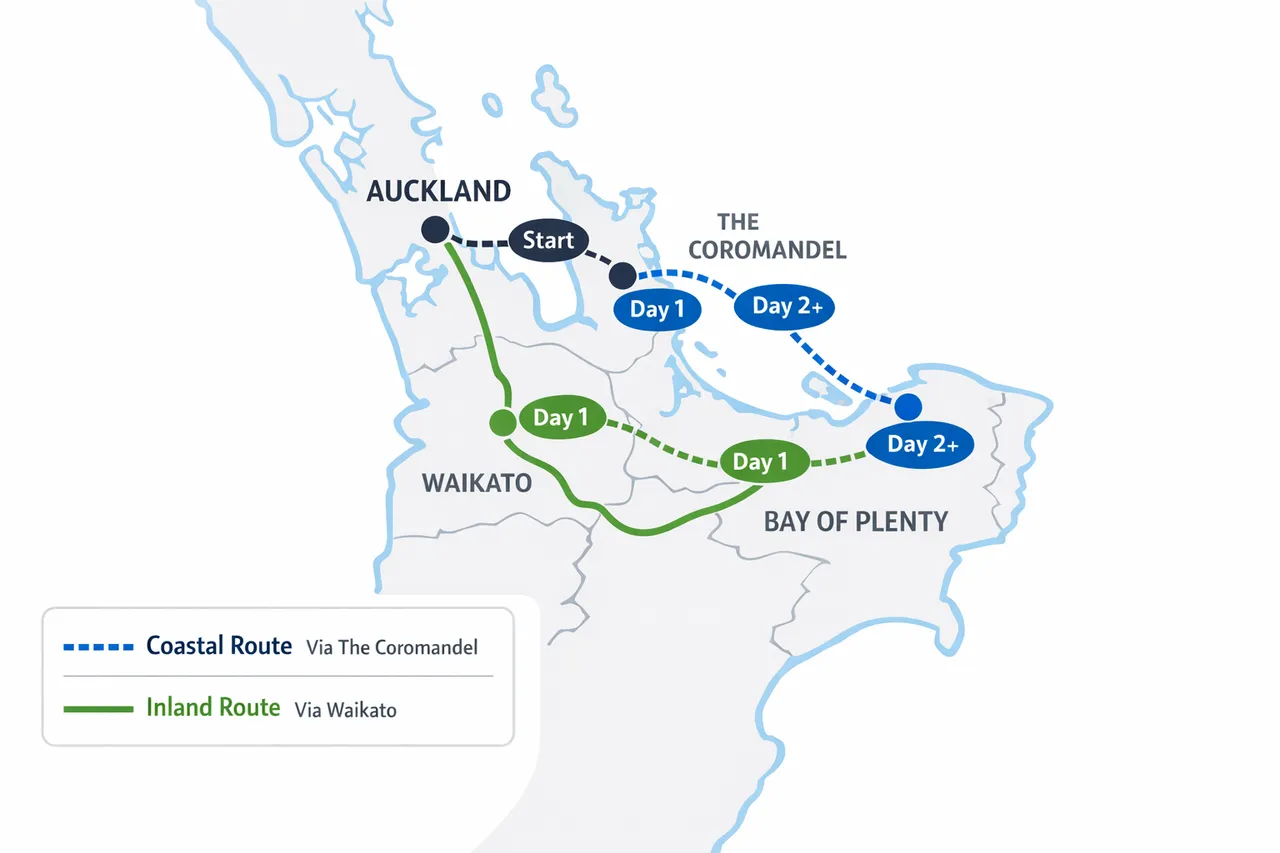

To make it concrete, think of Bay of Plenty (NZ) for example. For many visitors the trip is not “Bay of Plenty” first. It is:

- Arrive in Auckland (gateway)

- Decide between an inland path (Waikato) or a coastal path (The Coromandel)

- Then commit nights and spend somewhere that fits the story, pace, and purpose of the trip

In that kind of itinerary reality, Bay of Plenty is not competing only with “similar destinations”. It is competing with the structure of the journey, and with whichever adjacent place becomes the default next step.

The point is not that Bay of Plenty has an adjacency challenge. The point is that almost every destination does, and the same strategic patterns apply.

What the Destination Adjacency Challenge really is

The Destination Adjacency Challenge is the tension between two truths:

-

Visitors plan as a network of places

They think in routes, loops, day trips, and “while we’re there” add-ons. -

Destinations market as standalone brands

They present a single hero story and often avoid naming neighbors to protect brand purity.

That mismatch creates practical marketing problems:

- You do not show up in gateway-led planning, so you lose before you are considered.

- You get visited but not stayed in, so nights and spend leak elsewhere.

- You mention adjacent places inconsistently, so the overall narrative becomes confused.

Handled well, adjacency becomes a growth lever. Handled poorly, it becomes value leakage.

Why it matters to DMOs and place brands

Adjacency changes who you compete with

A destination’s “competition set” is not just similar destinations. It is also:

- the gateway city that captures most planning attention

- the adjacent places that slot neatly into the itinerary

- the “easy option” that requires fewer decisions

Adjacency shapes the visitor’s definition of value

People allocate time across a trip like a budget. The destination that feels easiest to integrate often wins nights, even if it is not the most differentiated.

Adjacency is where brand and product collide

Destinations are partly a story, but they are also logistics: transport, time, sequencing, energy levels, weather, and touring routes. Adjacency is the real-world layer that forces those tradeoffs.

The strategic goal: control the frame, not the borders

A useful way to think about adjacency is roles:

- Gateway: where visitors arrive and make first decisions

- Neighbor: an adjacent place that can be an add-on, route choice, or alternative

- Hero: the place you want to be the emotional payoff and the stay

Marketing works best when the messaging makes these roles obvious.

A simple narrative structure that travels well across destinations is:

Arrive (gateway) → Transition (ease) → Reward (hero destination) → Extend (neighbors as add-ons)

This structure is the antidote to adjacency dilution. It lets you reference adjacent places without handing them the spotlight.

Practical tactics DMOs can use to turn adjacency into an advantage

1) Map pathways, not just partners

Most adjacency problems persist because teams treat neighboring destinations as political geography rather than visitor behavior.

Start by mapping:

- top gateways and entry points

- common routes and touring loops

- top day-trip origins and “base” locations

- seasonal route shifts

The output is not a pretty map. It is a prioritised list of the top 3 to 7 pathways that actually drive trips.

Why it works: it aligns marketing with how the trip is purchased, not how the region is governed.

2) Create adjacency-safe messaging rules

Mentioning neighbors is often necessary. The risk is mentioning them in a way that makes your destination feel secondary.

A practical rule set looks like this:

- Name the gateway to reduce friction, then immediately restate your payoff.

- Name neighbors in planning contexts (itineraries, routes, “how to get here”), not always in brand hero headlines.

- Use “via”, “from”, “finish in”, “base in”, “add-on” language to keep roles clear.

Examples of adjacency-safe patterns:

- “Fly into X, then unwind in Y.”

- “Make Y your base, day-trip to Z.”

- “Finish in Y for the best version of the trip.”

Patterns to avoid:

- Flat lists of equal destinations (“X, Y, Z in one trip”), which dilute salience and ownership.

Why it works: it makes your destination the answer, and adjacency the justification.

3) Protect nights with “minimum and ideal stay” guidance

Adjacency often turns your destination into a pass-through. The fix is to define, and repeat, stay-length guidance that is tied to satisfaction.

- Minimum viable stay: the shortest stay that delivers the promise

- Ideal stay: the stay length that unlocks depth and spend

This sounds small, but it changes planning behavior. It gives visitors permission to allocate time properly.

Why it works: it converts “we can do it in a day” into “we should give it two nights”.

4) Design itineraries where you remain the base

If your destination can realistically be the hub for surrounding exploration, structure itineraries so that “neighbor experiences” are accessed outward, not inward.

A common winning pattern:

- Day 1: arrival and signature experience

- Day 2: second anchor experience (different theme)

- Day 3: optional day trip to an adjacent highlight

- Day 4: local depth and slower pace

Why it works: it lets visitors have variety without relocating their accommodation spend.

5) Turn adjacency into a comparison tool you control

Visitors already compare routes and adjacent options. A DMO can either ignore that and lose control, or meet it head-on.

One of the best adjacency tactics is explicitly helping visitors choose:

- coast vs inland

- slower scenic route vs faster direct route

- beach-heavy vs culture-heavy trip

When you design the comparison, you can ensure your destination is positioned as the place that benefits from the choice, not the place that is “also included”.

Why it works: it captures decision intent at the moment of itinerary formation.

6) Use gateway-led distribution channels

If the gateway captures planning attention, you need to show up there, even if you are not running those channels directly.

Think in terms of assets that partners can reuse:

- short “gateway to hero” story snippets

- route guidance and “best for” summaries

- packaged itineraries by duration

- a small set of signature experiences tied to bookings

Why it works: it inserts your destination into the planning surfaces where adjacency decisions are made.

7) Measure adjacency as a segment

Adjacency is frequently mishandled because it is not measured cleanly. It becomes opinion.

Track, at minimum:

- gateway-led content consumption

- neighbor-led entry paths

- assisted journeys that start with the gateway and end with your destination intent

Why it works: it turns adjacency from a narrative debate into an optimisation loop.

The Bay of Plenty example, simplified into a reusable model

You can swap Bay of Plenty for almost any destination and the logic holds:

- Gateway: Auckland

- Itinerary neighbors: Waikato (inland path), The Coromandel (coastal path)

- Marketing job: make Bay of Plenty the payoff and the stay, while using neighbors to reduce friction and increase confidence

The exact places change, but the pattern remains: travelers choose a gateway, choose a route, then allocate nights to the destination that best fits the story they are building.

Adjacency is where that story gets decided.

Closing thought

The adjacency issue is not a branding failure. It is a planning reality.

The destinations that win do not pretend they exist alone. They acknowledge adjacency, then control the frame:

- gateway as access

- neighbors as options

- your destination as payoff, depth, and nights

If you can do that consistently, adjacency stops being leakage and becomes a conversion engine.

Happy branding :)

The Destination Adjacency Challenge in Destination Marketing

The destination adjacency challenge explains why visitors plan trips through gateways and adjacent destinations, and how DMOs can use routes, itinerary framing, and stay-length strategy to capture more nights and spend.